How I Finally Got into Jazz; or, Records from Jared

I am currently obsessed with jazz. This is due entirely to the wisdom, taste, and generosity of my friend Jared.

For many years, I’ve wanted to get into jazz — a kind of music I had absolutely no contact with growing up, either from my parents or my friends. In undergrad, when everything in my life revolved around 70s/80s post-punk, I made a halfhearted effort, which left me enjoying Kind of Blue — surprise! — but not really getting anything else. In the years after, I would read books in which musicians I liked would say how influenced they were by jazz — Lou Reed crediting Ornette Coleman, Tom Verlaine Albert Ayler — and then I’d listen to the records they liked, dislike it myself, and continue on in my usual musical life.

With the advent of streaming in the last decade, I’ve at least had more opportunity to try jazz out without actually buying anything. Until recently, this hadn’t helped. Then, two years ago or so, I asked my friend Jared — one of the only people I know who listens to jazz (obsessively, I might add) — for some recommendations. We exchanged a few texts, which resulted in my downloading the following albums to my phone:

- John Coltrane, Interstellar Space

- Miles Davis, Agharta

- Andrew Hill, Point of Departure

- Charles Mingus, The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady

If you know these records, you can sort of see what Jared was thinking: that as someone who enjoys dissonant, challenging post-punk music, I would probably also enjoy dissonant, challenging jazz. Well, at first I definitely did not. Interstellar Space seemed horrible to me — noisy, grating, painful. Agharta was basically the same thing. (I feel similarly about both at the time of writing, actually.) I didn’t like Point of Departure at first, either, though it’s grown on me a bit more.

But oh my god, did I love The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady. It was my gateway drug. The thing that impressed me most was what a complete work of art it was: all of a piece, every song working with the next, every instrument telling a story, every voice contributing to the whole. I also just loved the sounds: the helicopter rumble of the contrabass, the reed instruments like wailing voices. Even before reading the liner notes (I was just streaming it on Tidal), I totally saw that there was a psychological dimension to it — that it was a confession.

It took me a long time to find anything else I liked nearly as much. I would try to listen to the Coltrane and Davis and Hill records to see if they’d suddenly snapped into place with the context provided by Black Saint, but they hadn’t. Instead, I got into other jazz-peripheral records like Yasuaki Shimizu and Mariah (about which you can read on my Test Tracks page), punk-influenced jazz like the Lounge Lizards (I was deeply into The Voice of Chunk despite its horrible title), Lounge Lizards-influenced hiphop like King Krule — and basically anything with a sax in it, like classic Roxy Music. Eventually I developed an affection of Eric Dolphy, especially Out There and his playing on Oliver Nelson’s Blues and the Abstract Truth.

It took vinyl to bring me the rest of the way in.

As I’ve briefly described elsewhere, when I got my Schiit DAC and my HE-1000 headphones, I briefly became convinced that digital sounded better than vinyl. In this time, I had many conversations with Jared, who gently insisted that I was wrong. As I’ve also described, I just about sold all my vinyl before doing a last-ditch A/B comparison that thankfully involved a really nicely-produced album by Yo La Tengo, which totally sounded better than the digital version.

After this awakening, I told Jared all about it, which led to a series of incredibly generous offers. He told me he was convinced that records produced on entirely analog equipment sounded best of all, and that early pressings sounded better than even the fanciest remasters. Recognizing that such records are often expensive, he told me I could take absolutely anything I wanted from his massive collection to listen to them on my stereo. Naturally, I was excited by the prospect.

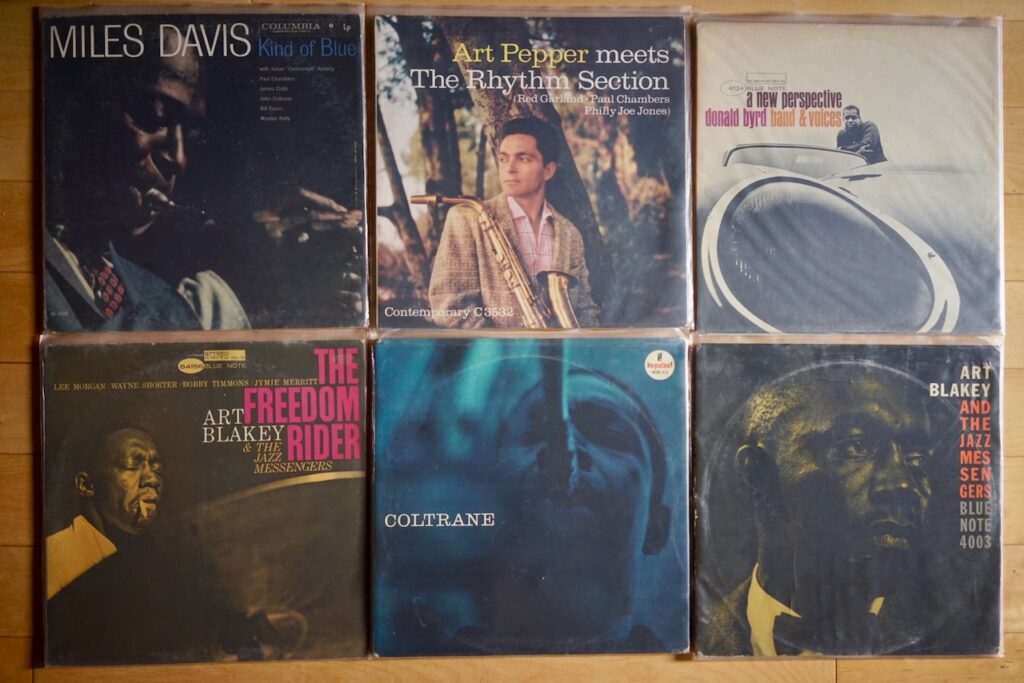

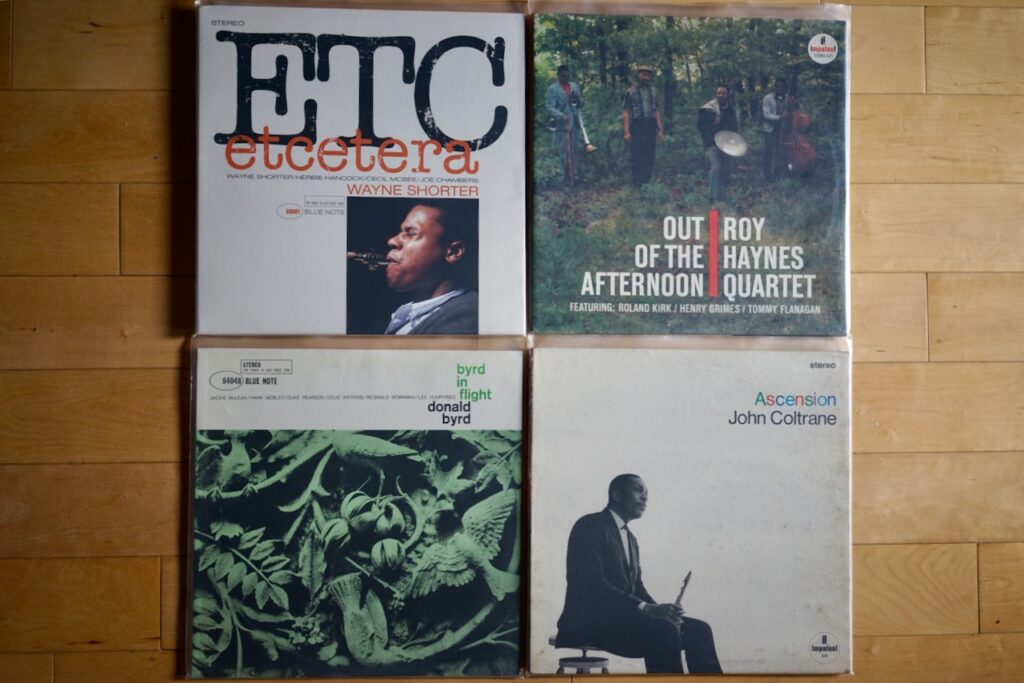

Now, Jared’s tastes lean mostly toward jazz, and his collection — started long before the vogue for vinyl — consists mostly of insanely rare stuff from the 50s and 60s. One day he invited me over to show me a sampling of what he thought would be especially nice-sounding records. This is when I heard the following words for the first time (seriously): “Van Gelder,” “deep groove,” “Plastylite.” If these mean anything to you, you’ll know that Jared was offering me the holy grail of analog fetishism: a bunch of original Blue Note pressings, some worth thousands of dollars.

There was other amazing and valuable stuff in there, too and most new words: “Impulse!,” “Strata East,” “Three Blind Mice,” “Contemporary Records,” “King pressing.”

In the last few months, I’ve had the opportunity to listen to some of the best-sounding (and most expensive) records in the world, at my own time, in my own room, on my own system. It’s been quite the experience — quite a gift.

(When I started looking up the value of the records Jared lent me on Discogs, I texted him, “Wow. You must really trust me!”)

I took that first batch home, and within a few weeks I was a jazz fan. I started to figure out what I liked in jazz — to see that there wasn’t just one big massive blob of music called “jazz,” but that (of course) it divided into lots of schools, periods, styles, streams, moods. I started to see what I liked and what I didn’t. I didn’t like stuff that was too out-there (I still don’t like Agharta or Interstellar Space or another Coltrane record in that first batch, Ascension). I didn’t like stuff that too straightforward, like Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section. I liked but was not obsessed with some classic hard bop by Art Blakey and Donald Byrd.

What I tended to really like was in the goldilocks position: a bit out there but not all the way. I tend to like stuff from the early to mid sixties. I like melodies and riffs — thus my obsession with Ornette Coleman, especially his first four records. But I don’t like formulaic playing, or a straightforwardly “entertaining” sound. I like pretty much everything by Charles Mingus, pretty much everything by Eric Dolphy, Jackie McLean’s Blue Note period, lots of stuff by Ornette. (Part of the fun of reading all the books I’ve read in the last few months is realizing all the ways these people intersect: Dolphy playing with Mingus in 1960 and 1964, Dolphy on the left channel in Ornette’s Free Jazz in 1961, Ornette playing trumpet on Jackie McLean’s New and Old Gospel in 1967…)

From the first batch, Clifford Jordan in the World totally rocked mine (and it’s a $2-300 rarity on Strata East, of course). From the second, the Prince Lasha Quintet’s The Cry! absolutely blew my mind — I still can’t get enough of it (another rarity, from Contemporary — damn). I just picked up a third batch today, and I have do doubt that incredible sounds await me.

Also: yes, wow, this stuff sounds amazing. I have yet to fully understand or appreciate Anthony Williams’s Blue Note debut Life Time, but the sound quality is insane: textures, sensations, feelings in my belly I’ve never encountered before. I already really liked Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come (obviously), but listening to it in a mid-60s Atlantic pressing was a staggering experience (the opening to Side A… oh my god, those twinned horns just jump out of nowhere and shake your entire skull in harmony with them). I haven’t fallen too hard for any of the stuff put out on Three Blind Mice, but I still can’t believe the sonic experience: totally dead-quiet vinyl, incredibly lifelike sound, especially piano, which feels like little mallets are directly striking your eardrum! For someone like me, for an artistic awakening to be accompanied by a sensory one — awesome music and incredible tech! — is about as good as it gets.

(I will go into plenty of detail on all this in future posts, I’m sure. For now, I’ll say that as much as I like original US Blue Note, I find the Japanese reissues to sound just as good or (mostly due to the excellent condition they’re in) better. In particular, the dead-quiet vinyl used in Japan in the 70s and the mastering done by King Records combine for some of the best-sounding stuff I’ve heard anywhere. The only thing I’ve heard that sounds as good is original Plastylite Blue Note and original Lester Koenig-produced records for Contemporary.)

Today I find myself obsessed both with vinyl and with jazz. I spend my days listening to records, tinkering with my turntable, scouring Discogs, flipping through used bins, reading books of music history, and writing about it all here. I’m not entirely sure it’s a healthy obsession — but I’m certainly enjoying it.

I have Jared to thank for all of it.